- Home

- S. C. Farrow

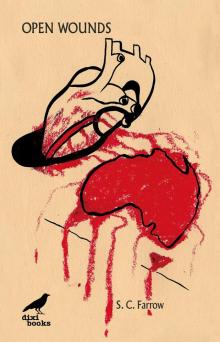

Open Wounds

Open Wounds Read online

S. C. Farrow

S.C. Farrow has been a writer and editor for over twenty years. She’s worked on everything from poetry to song lyrics, to fan fiction, to novels. She’s also written and produced several screenplays. Based in Melbourne, Australia, she has a Master of Arts degree in Creative Writing and runs a small editing service for writers and educational publishers. She also teaches creative writing at the Council of Adult Education (Box Hill Institute).

Open Wounds

Australian Short Stories

S. C. Farrow

Dixi Books

Copyright © 2018 by S. C. Farrow

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be used or reproduced or transmitted to any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information and retrieval system, without written permission from the Publisher.

Open Wounds - S. C. Farrow

Editor: Luise Hemmer Pihl

Designer: Pablo Ulyanov

Cover Design:

Printed in Bulgaria

I. Edition: February 2019

Library of Congress Cataloging-inPublication Data

S. C. Farrow, 19nn.

ISBN: ISBN 978-619-7458-42-8

1. Literature 2. Fiction 3. Trauma 4. The human Condition

© Dixi Books Publishing OOD

9, Pozitano Str. Entr. B, Fl 1, Office 2, 1000, Sofia, Bulgaria

Lebuser Strasse 14, 10243, Berlin, Germany

[email protected]

Open Wounds

Australian Short Stories

S. C. Farrow

Contents

Preface

Barbie Doll Bitch

Falling

Heat

The Roos are Loose

The Hanging of Jean Lee

Preface

The stories in this collection have been developed over a very long time-almost twenty years. Some of them are inspired by events that occurred in real life. Others are entirely fictional.

The characters in these stories exist in different locations and periods in time. They have vastly different lives, yet they are all connected by the devastating effects of physical and/or emotional trauma. Everything about a person, from the way they think, remember, learn, how they feel about themselves and others, and the way they view and understand the world, is affected and shaped by their experience.

Open Wounds is a collection of unflinching Australian short stories that shines a light on those moments in life that are as profound as they are traumatic.

Barbie Doll Bitch

‘You’re out!’ Patricia shouts.

‘I am not!’ Craig yells back as he runs like crazy to the next base.

Through the window I can see them laughing and having fun while I stand there, numb, waiting to talk to the Barbie Doll. I take a deep breath as I look inside the classroom and see her sitting at her desk sipping coffee as she reads. She’s got a red pen in her hand, so I guess she’s looking at our morning math test. I count my steps as I make my way forward, three, four, five, six. If I count, I can’t chicken out. I focus on her black hair, teased to the ceiling, and swallow hard as her perfume, sick and sweetly, crawls up my nose and down the back of my throat. If I can push it down into my stomach, I’ll be okay. If I don’t, I might be sick.

‘Why aren’t you outside, Merryn?’ she says, looking up at me with black-rimmed eyes.

‘I want to sit next to Sandra,’ I blurt out, wondering how she can keep her eyes open at all, with all that stuff on them.

She leans back in her chair as she looks at me, trying to figure out what I’m up to. ‘You already sit next to Patricia,’ she says.

‘I know. But I want to sit next to Sandra.’

Her eyes widen in their black-rimmed sockets and I think they’re going to bug out of her head.

The next day, I reach over to get the handkerchief from Sandra’s pocket. ‘Shhh,’ I whisper as I take it. I don’t want the Barbie Doll to see us. I never want the Barbie Doll to see us.

Sandra isn’t like the rest of us. She’s different. Special. She doesn’t look weird or anything like that. It’s just hard for her to learn things. And she doesn’t talk much. I don’t think she knows too many words, but she talks to me ’cause I listen and let her say what she wants to say without losing my temper or making her hurry. Her eyes are swollen, and her cheeks are streaked with dirt and tears. ‘Supersonic, idiotic, disconnected, brain-infected dumb-bell...’ That’s what they chant whenever she’s around. She doesn’t know what it means, but she does know what a punch feels like. I wipe the smear of snot from her cheek. Luckily the Barbie Doll is scratching something on the blackboard. While she can’t see me, she can’t embarrass me, and she can’t embarrass Sandra. I give Sandra back her hanky. Her long thumbnail scrapes my hand as she takes it. I love Sandra’s hands. Her skin is fine, like an expensive pair of gloves. Her fingers are long with manicured nails. Pretty hands. Not like mine. And she’s always so clean. Her long golden hair is always so neat in a ponytail. Her mother must love her very much. The Barbie Doll has fingernails like Sandra’s but hers are red, blood red, just like her lips.

After lunch, I get a fright when Sandra slips her hand into mine. I didn’t know she was behind me. ‘C’mon,’ I say, leading her up the corridor. ‘Let’s hurry up and get inside.’

But it’s too late. The chorus begins: ‘Supersonic, idiotic, disconnected, brain-infected dumb-bell. Supersonic, idiotic…’ And Kerry corners us at the classroom door. She looks down at our hands. I whisper to Sandra to go inside and sit down. ‘Whaddya hang around with her for?’ Kerry demands as she watches Sandra go.

‘You leave her alone,’ I snap.

Kerry shakes her head. ‘You’re dumber than she is.’

‘Yeah, well, she’s my friend.’

Kerry shrugs and walks off.

She is my friend. And I don’t need them.

In the classroom, a nasty smile twists the Barbie Doll’s mouth as she walks up and down the rows between our desks. I sit down quietly, praying she doesn’t see me. ‘Everyone is to write a poem for their homework,’ she says, stopping beside our desk. My heart pounds in my chest. I hold my breath and wait. ‘Everyone,’ she says, ‘except for Sandra.’ I sneak a peek at Sandra drawing in her picture book. Her thoughts are someplace else, far, far away from the apes and the hate that makes her cry. We all know that the Barbie Doll hates her. We overhear her telling the other teachers that Sandra should be in special school, that being here is a waste of time. At last, she walks off and I can breathe again. ‘The topic can be anything you like,’ she says, ‘but it must be ten lines or more and it must rhyme.’

I wish my thoughts were someplace else, someplace safe. But that’s not going to happen. It’s never going to happen.

It’s Monday morning and we sit at our desks drinking milk made warm by the early morning sun as we stood in the playground singing God Save the Queen in honour of some lady we don’t even know. But I know the days are getting longer and that soon it will be Christmas time. I play outside until the sun goes down and my grandma calls me in for tea. I don’t mind playing on my own, but Grandma says I need to make friends and that I really shouldn’t be so shy. I don’t know why.

I finish my milk and wonder where Sandra is. She’s away today. I wish she wasn’t. It’s time to read our poems. The Barbie Doll knows I hate reading out loud and when no one volunteers she makes me go first.

‘Go ahead, Merryn,’ she says from the front of the room.

Fifty-eight eyes bore into me as I take my paper and leave the safety of my desk. I stand at the front of the room and shake while the Barbie Doll glares at me beneath her pitch-black beehive. ‘You can begin,’ she says.

I want to. I try to. Bu

t the words are stuck in the back of my throat, and the edge of my paper is wet from the sweat leaking from my hands. My ugly hands.

‘Go ahead,’ she commands.

Now the words on my paper blur through my tears and fear. You bitch. You fucking bitch. I’m not allowed to say that at home, but I know what it means and that’s exactly what she is.

Later that day, a tennis ball rolls to a stop at my feet as I sit at the edge of the playground. ‘Nice poem, dopey,’ Craig says as he chases after it. ‘Sure Griggsy didn’t write it for ya?’ Craig is the most popular boy in our grade. All the girls love him.

‘No,’ I say, ‘She didn’t write it for me.’

‘Come on,’ Patricia puffs as she runs up beside him. ‘Whaddya doing? Get the ball.’ Then she turns to me. ‘Where’s your shadow today?’

‘I dunno,’ I say with a shrug. It’s true. I don’t know. I hope she’s back tomorrow.

‘You wanna play?’ she asks.

I look at her sideways. Do I wanna play? What does that mean? I’m suspicious, but yeah, I wanna play. I nod my head.

‘Okay,’ she says. ‘Go on Trudy’s team. They’re batting.’

It’s Friday today. The Barbie Doll’s been away all week. So has Sandra. I miss Sandra, but I love playing rounders. I’ve played it every day. Maybe I shouldn’t. I feel bad for having fun without her. I wish she’d come back.

All week, Miss Pearson, the substitute, had us making pink and white crepe paper flowers. Even the boys had to make them and today we finally learned why. At home-time, Miss Pearson handed out a notice.

Dear Parent,

Miss Clover is getting married at

St Stephen’s Church

Bernard Road

Mooralla

on Sunday 24th September at 4pm.

She would like to invite all her students to attend the ceremony.

Sincerely,

Miss Pearson (substitute)

It’s Tuesday today, which means the Barbie Doll is getting married next weekend. She hasn’t been back to school at all so Miss Pearson is still our teacher. I like Miss Pearson. She doesn’t make me read.

Sandra and I sit beneath the big oak tree in the playground. There was something wrong with her head but she’s better now and back at school. ‘S. A. N. N, Sandra, now put an N. Good. Now a D. Yep. Now an R. And now an A. Good, we’re finished.’ I hold up our gift, a horseshoe shaped bit of cardboard covered with white silky ribbon and decorated with pink ribbon roses and a card signed by both of us.

Sandra couldn’t get the hang of winding the ribbon around the horseshoe, so I did that. She wasn’t too good at making the ribbon roses either, so I did that too. It’s the most beautiful thing I’ve ever made. Grandma bought the ribbon for me, but I did the rest. We did the rest. Miss Clover will love it, and I will be at her wedding to give it to her. As soon as she sees it, I know she’ll change her mind about me and Sandra.

I miss rounders, but it doesn’t really matter. Sandra’s back and it’s just me and her again. Lunchtime seems long today.

Today’s the day. Sunday. Miss Clover’s wedding day. The crepe-paper arches look beautiful all covered in our crepe-paper flowers. Sandra and I haven’t been chosen to hold them, but we don’t mind. We stand at the end of the line, our arms linked with the other kids and wait to give Miss Clover our gift. I’m so excited. We’ve been here for ages. We’re not allowed inside the church. I guess we’d make too much noise. But I can’t wait to see her. Then something happens. Two men in suits open the church doors and a man with a big camera hurries out.

‘She must be coming,’ someone says.

‘She is coming,’ says someone else. ‘Look! There she is!’

Through the open doors, I catch a glimpse of her. Her eyes are still black, and her lips are still red, but today she looks different. Today, she looks like a princess. When the wind blows her veil the man she married stops it from covering her face then gives her a kiss on the cheek. I can’t stop staring at her. She looks so happy. How can someone so happy be so mean? After they have their photo taken their friends throw confetti over them, a rainbow of paper rain that means it’s time for them to leave. I grab Sandra’s hand and make sure we’re in the line on Miss Clover’s side. We have to give her our gift. Miss Pearson instructs the others to raise up the wire arches, just the way she showed us. We giggle and cheer as Miss Clover and her husband walk under our crepe-paper tribute.

‘Here she comes,’ I say to Sandra, holding out our horseshoe ready to slip it over her arm as she passes. But she doesn’t even look at me. And she doesn’t look at Sandra. She holds her husband’s hand as she walks right past us toward the big black car that’s waiting to take them away.

Sandra rubs her eye as she looks at me and asks, ‘Why didn’t you give it to her?’

Tears fill my eyes as I push her away. It’s all her fault. It’s all her fault that the Barbie Doll picks on us. It’s all her fault that the Barbie Doll hates us. And the others are right. She is dumb—and I hate her. ‘I don’t want to be your friend, Sandra. I don’t want to be your friend.’

The stink of perfume is long-gone from the classroom. And I’m glad. Sandra hasn’t been at school since I told her to get lost. That was three weeks ago. Miss Pearson said she wasn’t coming back at all. The Barbie Doll isn’t coming back either. I don’t miss Sandra now. I hope she’s okay, but I don’t miss her. Me and Craig and Patricia play rounders every day.

Falling

A cutting gust of wind blows through the King’s Domain gardens snatching breath from inside Olivia’s mouth. Gasping, she’s forced to stop and draw precious air back into her lungs. Russel doesn’t notice. He walks on without her. As she breathes deeply, another gust swells so fiercely it wrenches foliage from the majestic elms that line both sides of the pitted pathway. Transfixed, her eyes widen as she holds out her hands to the leaves that begin to swirl all around her. Never in her life has she seen anything so beautiful. It’s a breathtaking vortex where, for a single moment, time stands still, and she is alone with God. She knows this is His doing. That the leaves are a show just for her. Just for her. She hasn’t been to church for a long time, but she knows He’s watching her and that He hasn’t forgotten her. Suddenly, the wind shifts and sighs and scatters the shattered leaves across the ground. It’s a graceful swan song.

At last, she snaps out of her trance. When she looks up she realises Russell, with his shaggy blond hair, ice blue eyes, and a thumb hooked casually through the belt loop on his jeans, has stopped walking and turned to watch her. His look is hard. Not hard the way Graham looks at her with that stillness in his eyes and that anger on his lips. Even so, she doesn’t dare move as eyes slide down the length of her body and back up again. She doesn’t know what he’s thinking. She doesn’t know what he might say. Then without a word he turns away and keeps walking.

She swallows the fear that’s balled up in her throat and hurries to catch up with him. She should be on her way home, not trailing behind Russell as he makes his way to the Music Bowl. The others went home after the movie, but he didn’t want to go. He wanted to hang out more. She wanted to hang out too. She knew her mother would worry, but then again, she probably wouldn’t.

As they round a sweeping curve in the path, she spots the Sidney Myer Music Bowl nestled in the garden’s lush undulating slopes. A magnificent outdoor performance venue, the aluminium canopy looks like a sheet of white fabric elegantly draped over two giant vertical poles. Russel heads straight for the back of the building where the massive steel cables supporting the awning come together like strands of hair in a pony tail before disappearing into a concrete anchor buried deep in the ground.

She watches as he leaps up onto one of the strands. What the bloody hell is he doing? He glances back as if to ask if she’s coming. She hesitates. Is he crazy? Then casually, as if he does this kind of thing every day, he starts walking the tightrope towards the Bowl’s oblique roof.

Shit. What’s she going

to do? She looks left and right, then glances back over her shoulder. There’s an old couple coming this way. She looks back at Russell. He’s almost made it half way. Without thinking, she throws her leg over the nearest cable and straddles it as if it were a horse. She hauls herself up and stands precariously on the twisted steel. Buffeted by a gust of wind, she begins to wobble. She flails her arms as she tips further and further to the side. Her left foot slips off the curve of the cable. Then finally, with the threat of a hard fall looming, she tips back the other way. Balance restored. She takes a moment, and a big deep breath, then slowly, carefully, inches her way along the cable towards the back of the canopy.

At first, the climb up is nothing. Easy peasy. Like walking up the hill at the end of her street. Then all of a sudden, it gets steeper and harder to climb. Russell kind of crouches as he scrambles to the top, but she has to do it on her hands and knees. At the top, she lies on her stomach and stays perfectly still, too terrified to move. Beside her, Russell snorts and snuffles. The sound disgusts her, but she doesn’t say anything. He moves closer to the edge and leans over. What’s he doing now? She inches as close to the edge as she dares. From the top of the Myer Music Bowl, she expected to see a lot more than she can see. There’s nothing except the Shrine of Remembrance and a few tall city buildings. Then she looks down. Oh, shit. It’s so fucking high. The skin over her knuckles becomes as thin as tissue paper as she clings in a death grip to the edge of the canopy. The people in the seats below them…. They’re so far away she can’t make out their faces. Russell lets the gob of spit trickle from his lips. It dangles and stretches. It gets heavy and falls. She watches. Slow motion. It seems to take forever to hit the ground.

She wonders if that’s how long it would take for her to hit the ground.

She wonders why boys always spit.

The end of her nose is numb. Goose bumps prickle her skin. She wishes she’d brought a jumper. She slides back a few inches and rolls onto her back. The sound of fun made by Sunday strollers dissolves in the autumn air long before it reaches this height. Except for the occasional squawk of a passing bird, the embarrassing heave of her smoke-choked breath, and the coursing of her blood in the back of her ears, it’s disturbingly silent.

Open Wounds

Open Wounds